In a recent interview, Karlo Antonio Galay David shares his latest book and why writing local stories is important in today’s age.

Yadu Karu: What is the inspiration behind this collection of short stories?

KAGD: Proclivities emerged as a series of its own over a period of nine years. I began noticing that some of the stories I was writing were showing similarities in concern and style, so I started curating them into this series. To some extent this was inevitable: I grew up in Kidapawan and Davao being treated as something of a weirdo, so it was really only a matter of time before I started producing works that focus on that, on eccentricities, on the rituals which are born of trauma and which in turn shape those who do them.

YK: Among the stories which one is your favorite and why?

KAGD: Tough question. The author selling the book would like to say all the stories are my favourite so please buy the book, but the perfectionist writer and creative writing teacher in me would scream all of them are horrible (haha). But seriously, each one of the stories has sentimental significance to me. ‘Flourish’ and ‘Familiaris’ are some of my few happy ending stories, ‘Kuyaw’ will always be special for being Leoncio Deriada’s favourite story of mine, ‘In Manner Accustomed’ was my first award-winning work. Both ‘Familiaris’ and ‘Proclivities’ are introspections into Kidapawan and are based on personal experience. ‘Condign Restitutions’ started out as a story I had written when I was just five, and both ‘The Tenor These Delusions’ and ‘Summoner of Sorrows’ took almost eight years to finish. But ‘Arabella Raut the Eighth’ still feels like it’s the most technically accomplished story in the collection.

YK: What do you mean by your first line in the introduction: "We are all victims of our histories"?

KAGD: What happens to us shapes us, and does not always shape us in good ways. Whether that be terrible experiences leaving us traumas we carry long after the devastation or simply the limits of our past worlds that continue to keep our perspectives narrow. This is the reality which is reflected in both the proclivities of the main characters in the collection, and the often dehumanizing norms they struggle to resist.

This line was actually a quote I got from the writer DM Reyes during the 2011 Iyas Creative Writing Workshop in Bacolod. He was talking about how many Filipino writers are trapped with the English language. But I always found it sounded nice so decided to re-appropriate it for this meaning.

YK: You are an advocate of Mindanao Settler Literature. Can you explain what this is about especially to those who are not familiar with it.

KAGD: Long conversation, but in a nutshell I think Mindanao’s literatures should be recognized for the diverse body of texts – written from an equally diverse array of ethnolinguistic and cultural perspectives – that it actually is. That means literature written by Mindanao Settler writers should be read as such, and not as representations of and expressions from the perspective of the Lumad and Moro peoples (which they often depict). This collection and its stories openly acknowledge and embrace the fact that they are written from the Mindanao Settler perspective and dealing with Mindanao Settler concerns. Settler writers should be doing that, so they do not end up Settlerjacking – hijacking the discursive voices of the Lumad and Moro peoples.

YK: I noticed that your stories uses the local language specific to its setting. How does language define your story?

KAGD: Most of my stories try to stick as close as possible to the local linguistic realities from whence they emerge. In some, like ‘Familiaris’ and ‘The Summoner of Sorrows,’ I leave entire multilingual dialogue untranslated, while in another story, ‘Kuyaw,’ the entire thing is in Davao Tagalog. Ideas and their subtle nuances are bound by language, and you can only really translate words to a certain extent – ‘brayt’ has a different connotation to ‘smart,’ just as saying ‘agay’ expresses a different kind of pain as would saying ‘ouch’ and ‘aray.’ And some words are outright untranslatable – ‘lain,’ ‘kuyaw,’ ‘hilas’ among many others. Just by using ‘stuff’ in ‘Walang nagabili ng stuff ko dito’ implies that the speaker belongs to a certain socioeconomic background that would be lost in translation. I let these highly localized nuances – the idiosyncrasies of community really – come out in my stories.

This makes them part of my effort to write a Literature of the Specific, works that eschew ‘universality’ and try to be as particular and idiosyncratic as possible.

YK: Can you expound to us the Mindanawon critical theory of "Pakig-iniya."

KAGD: I haven’t had time to expand this concept yet (I had been working on it with architect Jon Traya), but as I have developed it so far (without publishing anything about it yet), Pakig-iniya is a way by which foreign texts can be read.

As Zeus Salazar pointed out, Filipino coloniality often looks at things – and reads and writes texts – from the perspective of outsiders – ‘pangkanilang pananaw,’ he calls it, or as I would put it in Bisaya ‘pag-inilaha.’ We write our stories so foreigners (usually Americans) can read them, we read everything the way foreigners would read. Salazar and his adherents often follow this critique with the alternative, ‘pangtayong pananaw’ (in Bisaya I would put it as ‘pag-inatoa’ or ‘pag-kinita’), asserting a Filipino nationalist perspective to looking at things.

As a critic of Filipino nationalism and Mindanao secessionist, I reject this ‘pangtayong pananaw’ (and all these recent philosophizing of terms like ‘atin’ and ‘tayo’) as homogenizing Manila-centrism that assumes a single perspective born of a single experience across the archipelago. We are all victims of our histories, but our histories have victimized us in diverse and often contrasting ways.

Instead of this homogenizing ‘inatoa’ that forces us to join a collective that doesn’t really understand, I say a way forward to dismantle ‘pag-inilaha’ would be to begin with the perspective of the self and the immediate vicinity – ‘Pag-iniya’ (‘iya’ having connotations both of ownership, identification, and nature – ‘iyahon ang nagkandaiyang kinaiyahan,’ own our respective natures). Textually this would mean we produce text and we consume text as who we are, first as individuals, then as part of the ever expanding communities we belong to.

‘Pakig-iniya’ – to take part in this ownership of self and nature with others – is another layer which emerges once we consume text written from other contexts. It is recognizing that the context is part of the text, and when reading texts with our own perspective we must also read the context from whence that text emerges and take it as prompt to reflect on our own context.

When we read Kobayashi Issa’s haiku ‘A world of dew is a world of dew indeed, and yet, and yet…’ we first understand that in Kobayashi’s context the ‘world of dew’ is a Buddhist metaphor implying the impermanence of things. Then we understand that he wrote this poem after his young daughter had died, and he was struggling to make sense of his grief even as he reflected on the Buddhist teaching. Pakig-iniya would be to reflect on how the dew does not have the same connotation of impermanence in our (in my case Kidapawan/Davao urban) system of meaning, and in fact impermanence is rarely reflected upon. We ask how a parent would process their grief in our parts, and ‘God has a plan’ would be the more usual response.

This is how I wish the stories in my collection would be read – to be understood as emerging from my context, but in doing so hopefully contributing to introspection in other contexts.

There is a Monuvu poem in ‘Familiaris’ that you could only read in this way:

‘Inis kahaan to minuvu no ko-iling to kosili, oyya su, inis kohaan od ngongaapan du pa rayon to linow’t Agkuu’

(The happiness of man is like an eel, yes because the happiness of man, you have to fish for it there in lake Agkuu).

The poem will not make sense to anyone not reading it from the Kidapawan context. But to those who come from the area, it will be immediately apparent that the poem is about impossibility – Agco is a boiling lake, finding eels there would be impossible. But an added layer of nuance is opened to those indigenous people living around the Lake, because they would know the legend of the eel supposedly living in the boiling water – whoever sees the eel is said to be granted happiness in life.

YK: How do you encourage other writers from the region to write local stories?

KAGD: I don’t want to bother, that’s their problem (haha), I know some of them like going around pretending to be ‘Writers of Colour’ in white people countries, but I will not stop them from being pathetic like that if they want to haha

To those who do want to explore their locale, my call has always been to not limit yourself to writing-as-depiction, but writing-as-articulation. You do not just show your place and its people as exotica in your stories, you have to be part of that place and people, understand its realities and concerns, and not only reflect that in your art but make your art as conversation about those realities and concerns. Local stories aren’t just about locales, they are written as and for locales.

In the whole collection, I think the titular story, ‘Proclivities,’ does this most –uprootedness, but also the burden of those whose responsibility is to be irrelevant, the need both to forget and remember, the need to resist the gravity of being inhuman – these are concerns I feel people in Kidapawan need to think about more, and far more than writing about Kidapawan in that story, I was writing for and to Kidapawan and its people.

YK: How does misrepresentation affect local literature?

KAGD: Misrepresentation – in all its layers – can serve to hijack local perspectives and promote distorted perceptions of a locale in wider audiences.

If a literary work is written by someone not from a place but the work is being anthologized or published as a text from that place just because it depicts that place (Antonio Enriquez’ Green Sanctuary, for example, being curated as ‘North Cotabato Literature,’ even though Enriquez is from Zamboanga), then that’s misrepresentation.

And that example also shows how distortions can be perpetuated. In Green Sanctuary, Enriquez invents Maguindanaon folklore around the Philippine eagle, and portrays the Maguindanaons as maggot eaters.

Of course you don’t need to be an outsider to perpetuate distortions and misrepresent perspectives. We do have local writers who, out of sheer ignorance to their own locale, end up depicting their locale in grossly distorted ways. There are also writers who end up being anthologized or curated as speaking for cultural communities they do not belong to, just because their works depict those communities.

This is why I openly disclose in the collection that my stories are Settler stories, and therefore should only be read as such.

YK: What is the best advice that you have received from a fellow writer?

KAGD: I’ve received a lot of important advice from fellow writers over the years, specially from mentors. But I think the most important advice came from one of my greatest influences, Macario Tiu. He was one of the first to tell me to keep writing about Kidapawan.

YK: What is your future writing plan(s)?

KAGD: Right now I’m focused on making the book a success, especially in Kidapawan and North Cotabato. I’m working with the book’s very talented illustrator, Kabacan-artist Raffael David Westram, in making this book sell. We want to send the message that literature and the arts can be viable careers in our province, and that successful writers and artists can come from Kidapawan and Kabacan.

For the future, I’m just starting to get out of a three year fiction block, so I’m still strategizing that. I’m planning to write a novel, a political thriller depicting Kidapawan’s political realities. At the same time I’m exploring both sudden fiction and popular fiction, and how I can start being more widely read in my hometown. Reaching the Kidapawan readership is the target.

______________

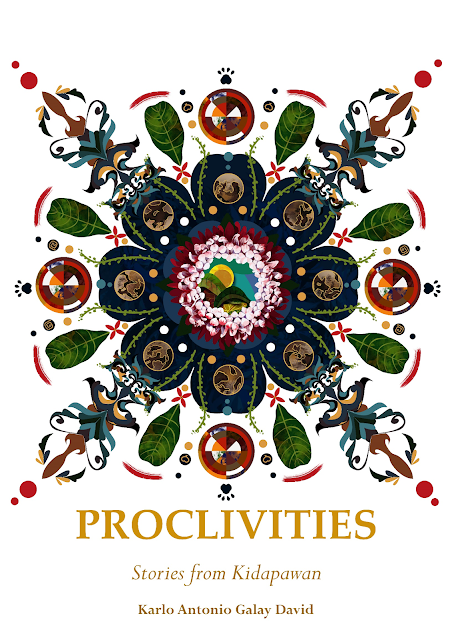

𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭'𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝑷𝒓𝒐𝒄𝒍𝒊𝒗𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒆𝒔: 𝑺𝒕𝒐𝒓𝒊𝒆𝒔 𝒇𝒓𝒐𝒎 𝑲𝒊𝒅𝒂𝒑𝒂𝒘𝒂𝒏?

Westram made a series of Mandala-like illustrations for each

of the nine stories in the collection.

The cover is a composite of all nine illustrations, and as

such contains images from all the nine stories.

Paw prints, talisay leaves, rubber seeds, chrysanthemum

petals - part of the pleasure of reading the book is spotting references from

the stories on the cover!

Just as the stories in the collection are attempts at

Mindanao Settler Fiction, West's illustrations (including the cover) are

conscious examples of Mindanao Settler Art.

These intricate artworks are deliberately decorative,

willingly following (but subtly subverting) the dominant motivation of

contemporary Mindanao Settler art to sell as decor, a mode we derisively call

the 'Wow Mindanao Aesthetic'.

There are angles which evoke a 'Mindanao' feel: the layout

and presence of leaves suggest the betel offerings on a Monuvu tombaa, while

the okir crests give a Moro touch.

But to these West adds distinctly Mindanao Settler (but no

less local) images: santan flowers, rubber seeds, and even abstract

multi-coloured discs suggestive of the iconic paintings of Settler artist

Kublai Millan (we called them 'Kinublay discs' when we were developing the

cover).

By doing so, West puts Mindanao Settler iconography at par

with the Lumad and Moro.

The images are arranged symmetrically but in a deliberately

cluttered look, eschewing coherence in a stylistic attempt at evoking the

constant inchoateness of postcolonial Mindanao (as opposed to the

oversimplistic 'Pinoy identity' deceptively perpetuated as coherent from

Manila).

The objects in each illustration are diverse, heterogenous,

and often have nothing in common but their shared place in the story - in other

words subtle stand-ins for the many peoples of Mindanao.

Not bad for a book cover!

(Posted by Karlo Antonio Galay David)

_____________________________________

𝑷𝒓𝒐𝒄𝒍𝒊𝒗𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒆𝒔: 𝑺𝒕𝒐𝒓𝒊𝒆𝒔 𝒇𝒓𝒐𝒎 𝑲𝒊𝒅𝒂𝒑𝒂𝒘𝒂𝒏 - if you are interested to buy the book, you can message Karlo Antonio Galay David FB page.

Comments

Post a Comment

The author encourages readers to post sensible comments in order to have meaningful discussions. Posting malicious, senseless and spam comments are highly discouraged.

Thank you for reading Yadu Karu's Blog.